Blog

Subscribe

Join over 5,000 people who receive the Anecdotally newsletter—and receive our free ebook Character Trumps Credentials.

Categories

- Anecdotes

- Business storytelling

- Collaboration

- Communication

- Corporate Storytelling

- Culture

- Decision-making

- Employee Engagement

- Events

- Fun

- Insight

- Leadership Posts

- News

- Podcast

- Selling

- Strategy

Archives

- March 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- July 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- April 2023

Years

What do we mean by tacit knowledge?

Most of our work here at Anecdote involves working with tacit knowledge. But it is clear that there is a broad understanding about what’s meant by the phrase. In the knowledge management world there are two camps: one that believes tacit knowledge can be captured, translated, converted; and the other that highlights its ineffable characteristics. I must admit I was for a long time firmly ensconced in the latter category and our white paper on “How we talk about knowledge management” reflects this view. But I realise now it is simply impractical to adopt an either/or perspective and so I would like to propose a way forward that focusses on why knowledge is tacit (remaining unspoken, unsaid, implied, unexpressed) and then based on these reasons we can start thinking about the appropriate approach to capturing or transferring tacit knowledge.

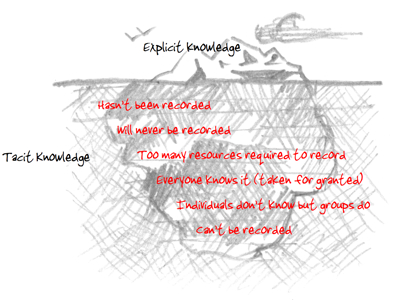

I think the iceberg metaphor is useful. Below the waterline lies an organisation’s tacit knowledge. Near the water surface lies tacit knowledge that’s easier to work with but as we go deeper the nature of the tacit knowledge changes, it becomes murkier and harder to see and grasp. As we increase in depth we can think of the different reasons why our knowledge is unspoken.

Hasn’t been recorded. Most organisations put their efforts in in dealing with this type of tacit knowledge. Probably because it’s easy. “Let’s find out what we know and then document it.” As a result wikis are popping up everywhere. Creating more explicit knowledge then creates a new problem of findability And as Peter Morville says, “what we find changes who we become.”

Will never be recorded. There are some things you know, that you could quite easily tell someone else, that you would never want to write down or be widely known. Imagine a diplomat who has an intimate knowledge of their counterpart’s peccadillos in an allied government. Perhaps not the type of thing that would be written down. More benign examples include stuff ups and when people are breaking the rules for the right reasons (or even for the wrong reasons).

Too many resources required to record. Sometimes it just takes too much time and effort to write down what you know. For one thing, when you write it down you have to assume a broad audience (not like a conversation where you are assessing whether the person you are taking to is getting it), which makes the task even harder. Imagine Einstein walking in the room and someone without advanced physics knowledge asking him to explain the general theory of relativity. It would be impossible for Einstein to provide a comprehensive answer because his knowledge requires stimulation in order to be forthcoming. Dave Snowden encapsulates this idea in his aphorism, “you only know what you know when you need to know it.”

Everyone knows it (taken for granted). Now we are getting into the type of tacit knowledge that’s more difficult to identify. This knowledge often represents the core values and beliefs in an organisation. It can manifest as metaphors. For example, I visited a investment bank in Sydney and their language revolved around gambling: “We can take a bet on that.” “Let’s roll the dice and see what happens.” “Everyone was poker faced.” Another organisation was fixated with traffic metaphors: “It’s a real roadblock.” “We got the green light.” “We have a clear roadmap now.” No one noticed how they were using these metaphors yet it guided their actions every day. I guess we call these things ‘culture.’

Individuals don’t know but groups do. Have you ever read Cognition in the Wild? It tells the story of the bridge crew of the aircraft carrier USS Palau and how together they can dock this enormous ship yet no single individual could describe how it is done. Many teams have this underrated and generally unrecognised this group-based ability.

Can’t be recorded. Much of our tacit knowledge falls into this category. The effects of this type of tacit knowledge (some would say the only true tacit knowledge) are displayed in our action and therefore it’s impossible to capture or convert it. The approach here is to become mindful and reflect of what is displayed—conversations, coaching, shadowing. Sure, we can video tape people undertaking tasks but time and time again practitioners have discovered there are qualities that are not captured and the task cannot be completed successfully. My favourite example is those white-coated gentlemen in France who test whether those humungous wheels of cheese have ripened. Using a little hammer they tap each one and know instantly which ones are ready to eat. How do they know? Is it the sounds, the bounciness, the smell? I recall a group of scientists set about to measure all these characteristics in order to create an automatic cheese ripeness testing machine but as hard as they might try they paled in comparison to the experience of the practised cheesemaker.

Technorati Tags: tacit knowledge

About Shawn Callahan

Shawn, author of Putting Stories to Work, is one of the world's leading business storytelling consultants. He helps executive teams find and tell the story of their strategy. When he is not working on strategy communication, Shawn is helping leaders find and tell business stories to engage, to influence and to inspire. Shawn works with Global 1000 companies including Shell, IBM, SAP, Bayer, Microsoft & Danone. Connect with Shawn on:

Comments

Comments are closed.

Cheese? What about the truffle detection systems 🙂

Tacit seems to hint at action, ‘knowing’ rather than ‘knowledge’, dipping the toes back into Polanyi, Dewey and James – gawd, there’s so much to read! Or does reading only tap the left-brain, and action dig deeper into the “habit” forming parts of the brain that we may choose to call practice (situated in a community, team etc.) these days?

Hi Shawn,

I too find the iceberg a very compelling metaphor. One drawback I have found with it however is the need to represent the continuous evolution of tacit to explicit knowledge, as if the water were constantly lowering and the bottom of the iceberg constantly growing. I often use the example of Special Relativity which was once inconceivable, then only conceivable by one, then a few, and now is taught in high school. Hmmm, perhaps more paradigm shift material than tacit/explicit. I have tried other metaphors such a a boiling pot of water and maps of the ancient world but nothing seems to quite capture it for me.

Also, I wonder if there is room for a hierarchy of explicit knowledge on top of the iceberg. As in, known now, googleable, ungoogleable, known but forgotten (a la Jane Jacobs’ Dark Age Ahead). Just thinking out loud.

-Steve

Great to see you back Ken. I hinted at my thought about practice and experience in the last line because that’s were tacit knowledge lives, in our experiences and practices. As you say, it’s dynamic and alive and like jelly, hard to pin down and when you try you typically end up with a mess.

Hi Steve, the progression you describe of special relativity reminds me of Max Boisot’s i-space where he describes how knowledge tracks around a cycle starting from very few people knowing, mostly specific knowledge, mainly tacit to becoming more available, more explicit, more general. It’s a useful model. His book is called Knowledge Assets if you haven’t seen it.

I do worry a bit about introducing hierarchies because someone will say, “Let’s do the easy stuff first and leave the harder stuff to later” thinking that you can unpick these categories when in practice everything is interlined. The data, information, knowledge hierarchy still hurts KM practitioners today for this reason.

Shawn,

This is a powerful way to codify such a complex sense of knowledge. When you group these along patterns, as you did, it leaves a small portion as a truly undeliverable.

I think the “Hasn’t been recorded” and the “Too many resources required to record” are very much connected. In implementing a wiki or other collaborative content efforts it is very challenging to convince users that is worth their time (resources) to contribute (record) what they know. For most it can seem too daunting and repetitive to record what they perceive as commonsense.

Great metaphor! Thanks!

Shaun.. Like other commenters, I too think it a useful metaphor / exploration of tacit knowledge. I’ve seen methaphor used a few times now, and I wonder if you know the originator / authorotative source if there is one. I work in a highly analytic / research oriented culture where “quote your source” is important.

Thanks.

Hi Shawn – I find this really quite helpful in the way it categories ways of talking about tacit knowledge, and the continuum you are suggesting from ‘not recorded’ to ‘unrecordable’.

I’m interested in why you think it’s “simply impractical” to be either/or about tacit knowledge? Is this just a pragmatic change of language on your part? I suspect from the comment that “some would say” that knowledge that can’t be recorded is the only true tacit knowledge that this might be the case…

Cheers,

Stuart Reid

The impracticality of the tacit/explicit dichotomy surfaces when you try and come up with initiatives to share knowledge. Two categories of knowledge is not fine enough to decide what to do. When you break it down further and consider why knowledge is unspoken then the initiatives become more obvious.

The unrecordable view of tacit knowledge is one I personally hold but it’s difficult to educate an organisation when they already believe, which seems to be the majority of people, that tacit knowledge is just sitting there waiting to be translated into explicit. I’m most interested in the unrecordable tacit knowledge and have been exploring ways to transfer it, such as using decision games. Again, I just being pragmatic and doing what I can to make a difference with my clients.

Thanks Shawn, very interesting. I’m with you on the tacit = unrecordable, but agree that it’s helpful to have a continuum of more fine-grained language to describe other types of unrecorded knowledge.

Stuart